Age-differentiated measures for optimized cost-benefit in the fight against Covid-19

Samuel J. Sender, Associate Professor, discusses in an article originally published on The Conversation the optimization of restrictions to minimize costs to the community, while maximizing the effectiveness of measures for individuals.

Economic decisions, whether individual or collective, must be based on an analysis of the costs and risks associated with each policy. Without accurate analysis, there is a risk that the feelings of a minority will dictate the decisions made for the majority.

Public policies generally differentiate between groups within the population. While Covid-related public policies did differentiate between economic players (companies and employees, depending on the sector) in their "recovery plan" component, no differentiation was made between different categories of people in the "prevention/health" component.

However, this is essential in the current crisis. Individuals are as unequal in the face of disease as economic players are in the face of recession. It is therefore essential to take their differences into account when drawing up public policies.

To determine which measures are optimal, the aim is to minimize the costs to society (minimizing economic losses and the cost of healthcare expenditure), while maximizing the effectiveness of the measures for individuals (finding the most effective action to reduce the number of sick people).

Working people, the big losers of restrictions

From this base, we can separate the adult population into two categories: retired/seniors and working people, who can be approximated as over- and under-60s.

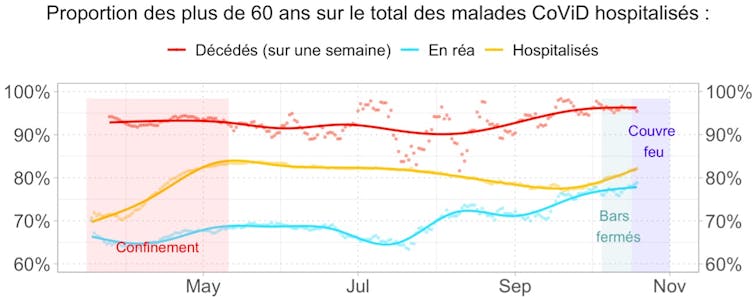

Retired people are more vulnerable to illness, accounting for over 80% of hospital admissions, but in our pay-as-you-go pension system, they are less sensitive to economic downturns than the rest of the population. Compared to working people, especially the youngest, their health has been more affected by the virus, with very significant probabilities of hospitalization and death.

Greater awareness and protection of pensioners would have prevented the saturation of intensive care units, saved the lives of the majority, and eased the pressure on nursing staff, given the high mortality rate among Covid pensioners in hospital.

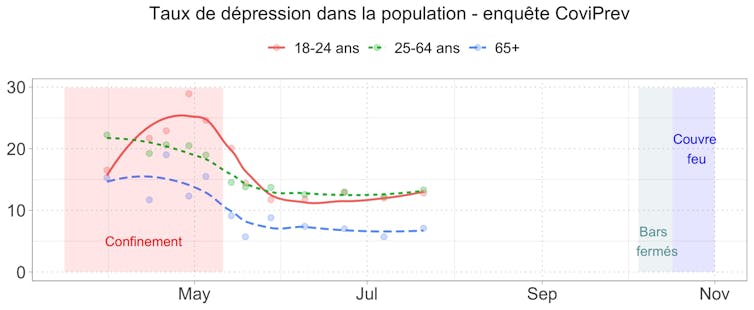

Working people, on the other hand, derive their income from work and are naturally the most dependent on the economy, especially the youngest. Yet, as the CoViPrev surveys show, it is this category that suffered the most psychologically during the confinement period, even though the probability of a Covid-19-related death in their age bracket is not statistically significant: it cannot be distinguished from natural mortality trends over the past decade.

Working people as a whole therefore have everything to lose (psychologically and economically) from restrictive measures, for an insignificant gain in terms of health.

The economic slowdown and uncertainty are also destroying human capital, particularly among the young, with a long-term impact. In the short term, the cost of the recession and economic support measures is extremely high: 9% of recession represents a value destruction of 225 billion euros in 2020 alone, to which must be added the 100 billion euros of the stimulus plan.

Risks and costs among seniors

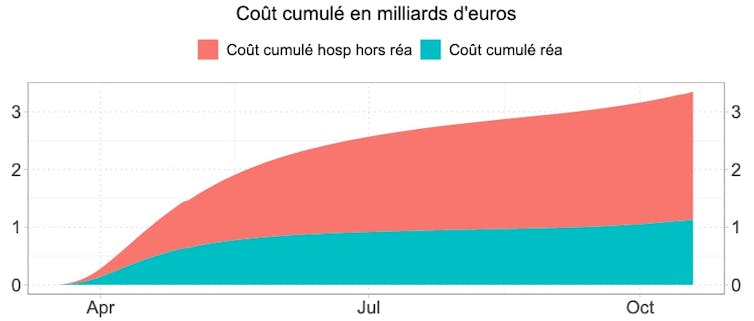

The cost of hospitalization and resuscitation is much lower: according to our estimates, it would be around 5 billion euros for the year 2020, and could reach 15 billion euros annually in a first-wave crisis scenario. With measures specifically targeting better protection for seniors, hospitalization costs could be 80% lower. As for the impact on the economy, by lifting barriers on the working population, this too could be reduced by 80%.

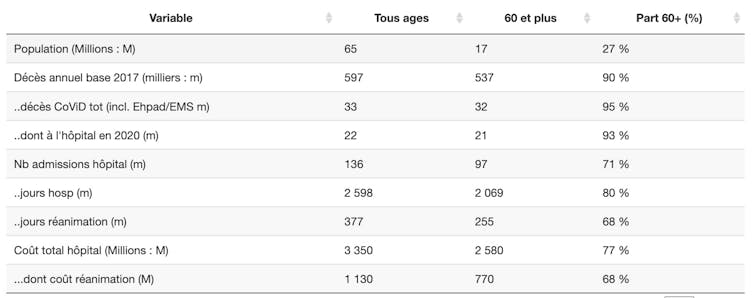

Table 1 shows the share of the over-60s in various statistics. They represent 27% of the population, 90% of deaths in normal times, and over the year as a whole 93% of Covid deaths for 77% of hospital costs (80% of hospitalization days, and 68% of intensive care days).

If we break down senior citizens into those over and under 70, the 60-69 age group consumes as many hospital resources as the under-60s, and the over-70s consume more than the under-70s as a whole. The length of hospital stays increases with age, as does the probability of death: for each hospital admission, it is less than 1% for 20-29 year-olds, and more than 25% for the over-70s.

Curfews: how targeted?

The point here is not to arbitrate on what care should or shouldn't be provided, but to realize that the risk to the elderly population is so great that one epidemic wave is enough to saturate the country's entire resuscitation capacity.

In the absence of complete border closure and citizen control, it doesn't seem possible to eradicate the virus using strict "Chinese-style" measures. Such measures generate costly waves for both individuals and the economy.

While the introduction of a curfew from 9 p.m. has the merit of being less brutal for the economy than the confinement of the first wave, it does not target the primary mortality factor - the contamination and mortality of senior citizens.

More than ever, therefore, it seems necessary to develop communication aimed at the elderly and frail about the dangers of Covid contamination. Given the active circulation of the virus, it is undoubtedly more appropriate to recommend (or even impose) that frail people apply the same hygiene and precautionary measures in private gatherings as those imposed in public meetings and places.

The full set of graphs and statistics, updated daily, can be accessed by clicking here.

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image by pikisuperstar on Freepik