Air travel will never be the same

Rene Rohrbeck, Professor of Strategy at EDHEC, discusses the future of air transport in an article originally published on The Conversation.

“In 65 days, traffic has lost what it took 65 years to gain.” This was the shocking statement made by Carsten Spohr, CEO of Lufthansa, in an address to company shareholders on May 5.

Last spring, the number of Lufthansa passengers were just one per cent higher than they were the previous year, a figure that illustrates the scale of the crisis, matching the bleak outlook for the global sector. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) predicts a drop of 55% from the 2019 passenger numbers around the world, including those months in which traffic returned to a normal level.

Despite this unprecedentedly intense crisis, a future without air transportation remains unthinkable. But what will it look like after the crisis?

To answer that question, the EDHEC Business School launched a project in

September 2020 on the future of the air transport industry. In this project, 13 partners in the air transport ecosystem use a variety of forecasting methods to study some scenarios for the future of the industry. These partners include two large airports, two international airlines, two manufacturers of aircraft and equipment, an industrial association, as well as some travel agencies and technology suppliers.

As an intermediate step, the project has identified four factors that will determine the future of the air transport sector: business travel, the regionalisation of flight routes, hub and spoke networks, and flight shaming.

Return to normal for business travel?

Seen by many as an essential motor of economic growth, business travel has benefitted for several years from a sort of magic aura that transforms physical meetings around the world into commercial and economic opportunities. It has also been an important driver of growth for the airline industry.

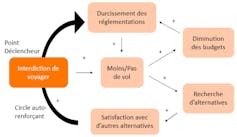

However, it is possible that business travel will not return to its pre-crisis level. Travel bans, imposed by states and companies, might be a point of departure for a self-reinforcing cycle that strategists are looking for to identify exponential changes.

As the feedback loop diagram above suggests, bans on travel suggest fewer or no

flights, which reduces travel budgets and provokes a hardening of travel regulations, many of which will remain in place even after the travel bans have been lifted.

If such a cycle stops within four weeks, the new behaviours will not have had the time to adapt, and the system will generally return to its initial state. But the longer the crisis lasts, the more likely it is that system changes will become permanent. The lack of business travel and face-to-face meetings has now led to the adoption of mass-market alternatives such as videoconferencing, virtual collaboration, online whiteboards, etc. If these alternatives can show that they can increase productivity then business travel will become an exception for meetings, as it was 65 years ago.

From globalisation to regionalisation?

Since 2005, globalisation has showed signs of slowing. Company internationalisation strategies are focused more and more on local responsiveness and less and less on control by and dependence on international head offices.

Global trade tensions such as that between the United States and China can also contribute to the slowing down in intercontinental movements. The Covid-19 crisis might accelerate this trend and encourage regional trade and supply.

A recent study shows that one of the significant reactions to the Covid-19 crisis has

been the relocation of supply chains and in particular, an emphasis on the use of regional ecosystems. This may become permanent, reinforced by the low frequency of international trips.

Recent statistics from the International Civil Aviation Organisation show that while inter-regional trips are beginning again, from an average of 250 million passengers before the crisis to 100 million today, the number of international travellers has risen to just 20 million, well below the 160 million it was before the crisis.

Is this the end of star networks?

Interestingly, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has been felt differently by low-cost carriers (LCCs) such as Ryan Air and EasyJet, and the traditional network carriers (TNCs) such as Air France, Lufthansa, and Singapore Airlines.

The TNCs rely on central hubs where short-haul flights are linked to long-haul flights which, with their larger planes, are economically more attractive. This star model, also called hub and spoke, creates powerful network effects, allowing large airline companies to achieve economies of scale and to put up powerful barriers to new arrivals.

These advantages for the TNCs come at the price of customer acceptance because the itineraries involve connections. In normal times, they can be questioned on environmental grounds and can be seen by passengers as an inconvenience. But in times of a health crisis, the hubs are key risk zones in a passenger’s journey because it can be difficult to guarantee the rules of social distancing in airports.

The interdependence of short- and long-haul flights is also a huge obstacle to recovery. For the TNCs, the lack of long-haul flights means that the short-haul flights must be reduced. The lack of short-haul flights in turn makes it impossible to fill the large long-haul aircraft.

The low-cost and full-service carriers operating on a point-to-point model can be more responsive, by opening and closing routes in response to fluctuations in demand. Most TNCs are adopting a strategy of waiting out the crisis and restarting their hub and spoke model. But to avoid breakdowns in their long-haul refuelling systems, they must keep open unprofitable routes. In the majority of cases, this leaves them dependent on state aid. The question is how long this strategy can be maintained and how long shareholders will be ready to cover the losses.

It is not surprising that some TNCs are rediscovering holiday travel with their point-to-point offers. “Never before have we included so many new holiday destinations in our programme. It is our response to our clients wishes”, explains Harry Hohmeister, for example, member of the Deutsche Lufthansa AG board of directors.

And what about flight shaming?

Growing consciousness of the environmental impact of air travel led to the emergence in Sweden of a flygskam (flight shaming) movement, aimed at avoiding air travel, which has now gone long beyond the Swedish borders.

Moreover, certain signs indicate that confinement regulations during the Covid-19 crisis have increased people’s desires for a quieter life. This raises questions about the cosmopolitan lifestyle that the middle classes adopted so easily. This remains at the heart of the preoccupations of air travel world actors, even if their real influence on consumer behaviour is not yet easy to measure.

To sum up, our work reveals that these four change factors presage a more radical transition in air transportation than in other sectors. While we should remain cautious about expectations when the uncertainties remain so great, it seems that post-Covid scenarios will emerge around these four elements. These different possible scenarios will be the object of further study in our research project.

This article was co-published with The Conversation France France under the Creative Commons

licence. Read the original article.