The best weapon in the fight against Covid-19: respecting barrier gestures

In an article originally published on The Conversation, Associate Professor Samuel J. Sender discusses the least economically costly solutions to the Covid-19 epidemic.

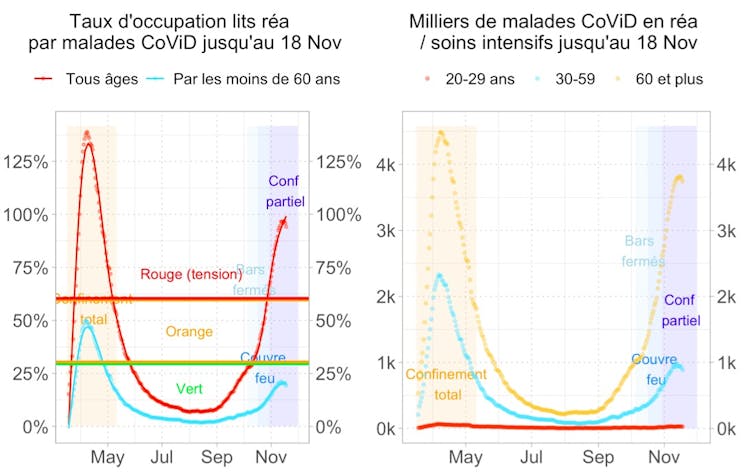

If we compare the two epidemic waves, given the apparent decline in the number of Covid-19 patients in hospitals, the second wave may have been better controlled than the first, at a lower cost.

Santé publique France data (as of November 18)

In its November 9 economic update, the Banque de France estimated that the loss of GDP for a typical week of activity (compared with the normal pre-pandemic level) would be : - 4% in October (the second fortnight of which was marked by the implementation of curfews in major cities) and - 12% in November (marked by the implementation of the second, partial, containment), compared with - 31% in April (first, total, containment).

The measures put in place to curb the second wave partially drew on the lessons learned from the first wave: by allowing business to continue in part, they enabled the economic shock to be three times lower than during the first wave, with less saturation of healthcare systems.

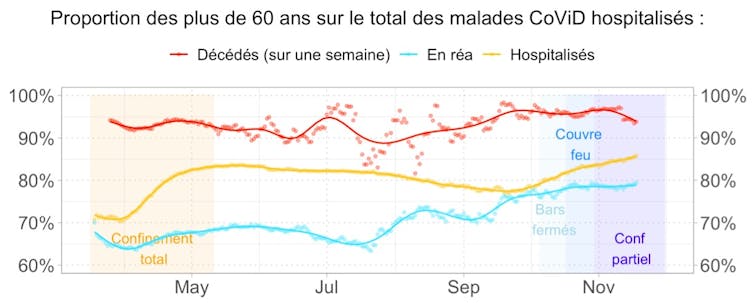

However, the restrictions did not primarily target frail populations: even more than in the first wave, pensioners accounted for the bulk of hospitalisations, resuscitations and deaths. According to data from Santé Publique France, the proportion of senior citizens in intensive care was even higher than in the first wave, despite the fact that their frailty is well known and the progression of the infection can be seen from the rate of infection.

This graph shows the evolution of the proportion of senior citizens in hospitalizations, resuscitations and deaths. The proportion of seniors in intensive care is rising steadily: recent policies do not seem to have protected the most vulnerable.

Santé publique France data (as of November 18).

Recent data show the effectiveness of the curfew: the restriction measures of the first wave had led to a slowdown in new hospitalizations after 15 days, and these also slowed less than 15 days after the October 17 curfew.

The reality of confinement in early November does not allow us to know whether simply maintaining the curfew would have been sufficient to curb the epidemic. These data do, however, allow us to question the place of the various measures in the prevention arsenal.

Insufficient adoption of barrier measures

The mechanisms by which the virus spreads are now well known: airborne particles and touch. Barrier measures such as wearing a mask, social distancing and individual hygiene measures seem, in theory, perfectly effective.

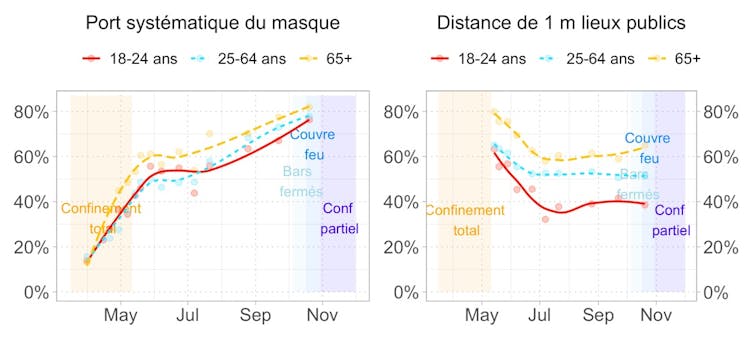

To explain the acceleration in contamination of vulnerable people in September and October, we therefore need to consider both the systematic adoption of barrier measures and their effectiveness in real-life situations.

The first observation is that barrier measures are not systematically adopted, even by the over-60s. 80% of them systematically wear masks in public places, and only 60% respect the one-meter distance in public spaces.

This is the percentage of respondents who say they systematically adopt barrier measures in public places. Wearing a mask is more widespread, respecting a distance of 1 meter less so.

Data from Santé publique France, CoViPreV monthly survey (as of October 21).

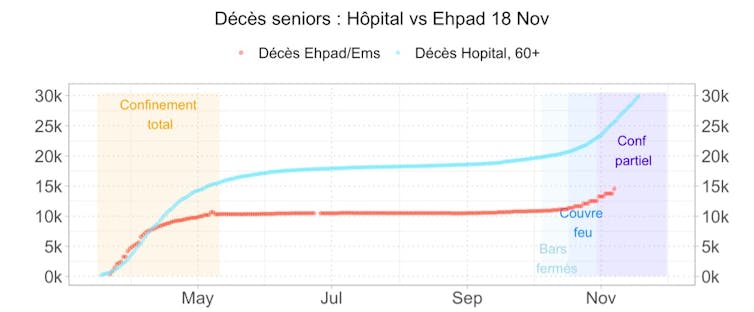

Observation of the situation in Etablissements d'hébergement pour personnes âgées dépendantes (Ehpad) suggests that the overly partial adoption of barrier gestures is one of the causes of the second wave. In October, mortality among senior citizens was six times lower than during the first confinement in Ehpad, whereas it was once again exponential in hospitals.

However, Ehpad have adopted a strict sanitary protocol, and despite the reauthorization of family visits from April 19, the cumulative number of Covid deaths has stabilized: mortality was almost nil until mid-September. This seems to indicate that compliance with barrier measures is far more effective in the short term than confining populations, and at a much lower cost.

Ehpad data have been brought forward by 10 days to visualize the similarity of dynamics at the start of the first wave, then the lower mortality in Ehpads from the widespread adoption of barrier gestures. Santé publique France data (as of November 18)

The strategies of containment followed by "test-trace-isolate", used successfully in Asia, appear to be less effective in France. Indeed, according to Santé publique France estimates available on the Anti-CoViD application (called StopCovid in the previous version) as of November 11, the application has alerted almost 10,000 people to a risk of contamination in 2020, out of almost 20 million tests carried out and a total of almost 2 million confirmed cases.

Better information

In the event of an epidemic wave, if we can't isolate carriers, we need to give vulnerable people the means to protect themselves. Precise information on the risks involved is therefore essential if barrier measures are to be adopted.

With this in mind, we have developed a tool that calculates the probability of hospitalization for a given individual, based on age, comorbidities and behavior.

To encourage vulnerable people to stay indoors, social, legal and financial support measures (right to opt out and short-time working), and even logistical measures (home deliveries and care, masks that offer better protection than conventional masks), could also be taken to enable them to opt out voluntarily. These measures, which have not yet been costed, would have a derisory cost for the economy compared with the cost of widespread confinement.

These analyses are supported by a more comprehensive set of graphs and statistics, updated daily. It can be accessed by clicking here and here.

This article is republished fromThe Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image on Freepik