The reform of the pension system, or the story of a new hold-up by the papy-boomers

Arnaud Chéron, Director of EDHEC Economics, EDHEC Business School, in an article originally published on The Conversation, of the pension reform objectives.

The final word is in: the government's plan to reform the pension system combines two objectives, through a systemic, point-based reform.

The first of these objectives is presented as that of social justice through the universality of the scheme: the aim is to converge, within a single scheme, the current general scheme and the 42 existing special schemes, with the principle of an accumulation of points (pension rights) whose value will be the same, whatever the occupation carried out; bonuses on this accumulation could however be granted according to the arduousness of the work performed.

Implacable financial logic

In addition, the switchover of special schemes to the new system is planned to take place at a later date than for contributors to the general scheme: while it will apply to private-sector workers from the 1975 generation onwards, the first generation concerned will be that of 1985 for SNCF drivers, for example. Convergence towards standardization will therefore be gradual, so as not to "over-penalize" individuals who have made career choices linked to the specificity of the associated pension scheme. Similarly, a number of specific features will be maintained for certain high-risk professions (firefighters, military personnel or police officers).

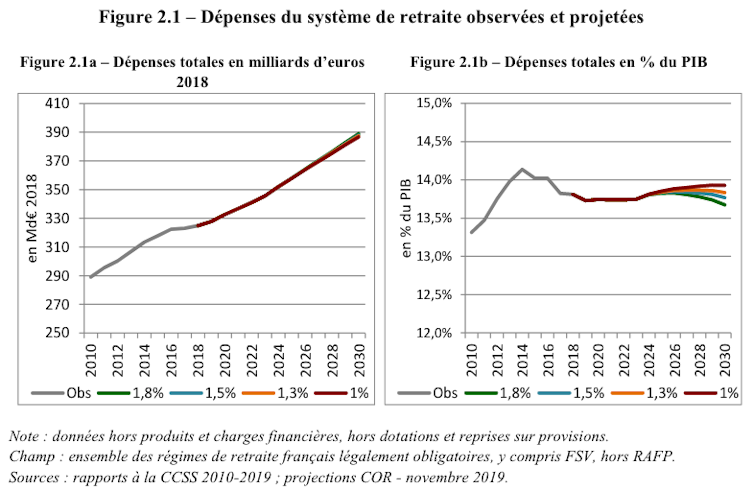

The second objective is to achieve financial equilibrium, as the system currently remains structurally in deficit, with pension expenditure at 14% of GDP and revenue at 13%.

Forecasts by the Conseil d'Orientation des Retraites (COR) indicate that by 2025 this deficit will be equivalent to between 7.9 and 17.2 billion euros, depending on the economic scenario adopted. In the government's plan, the objective of financial equilibrium is mainly embodied by the introduction of a pivot age of 64, two years higher than the legal minimum retirement age.

The current confusion, and the risk of a confluence of different types of social protest, certainly stem from the government's determination to pursue these two ambitious objectives simultaneously, adding parametric reform to systemic reform.

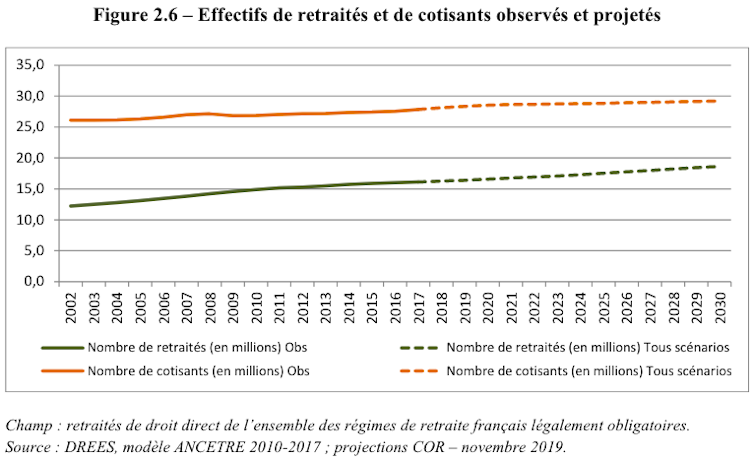

Financial logic, for its part, seems implacable in the face of the challenge posed by demographics: the ratio of 20-59 year-olds to 60+ year-olds is falling steadily, and will continue to do so: from around 1.8 at present, it will drop to 1.3 by 2070 (compared with 2.76 in 1990).

Intergenerational iniquity

A return to financial equilibrium therefore depends at least in part on age-related measures. But the problem currently posed by social protest (and in particular the CFDT) is rather that of synchronizing financial measures with a systemic reform designed to make our pay-as-you-go pension system fairer.

When it comes to fairness, however, there seems to be one major omission from the reform: current pensioners. The plan is to make working people bear the brunt of the reform, whereas today we are already confronted with a major intergenerational inequity, on two levels.

On the one hand, papy-boomers (the baby-boom generation that has just retired) have contributed relatively less, via their contributions, to the pay-as-you-go system to finance the pensions of their elders (fewer in number), than working people do today. On the other hand, they have benefited from a substantially lower retirement age than their descendants.

The government's choice is to reduce inequalities between working people and future retirees, without making current retirees, at least the most affluent among them, contribute. This is probably to avoid any further social unrest, but it is nonetheless highly questionable.

A contribution from the most affluent pensioners could facilitate this transition: longer careers must be able to take place under conditions that are conducive to employment and, what's more, not on the cheap.

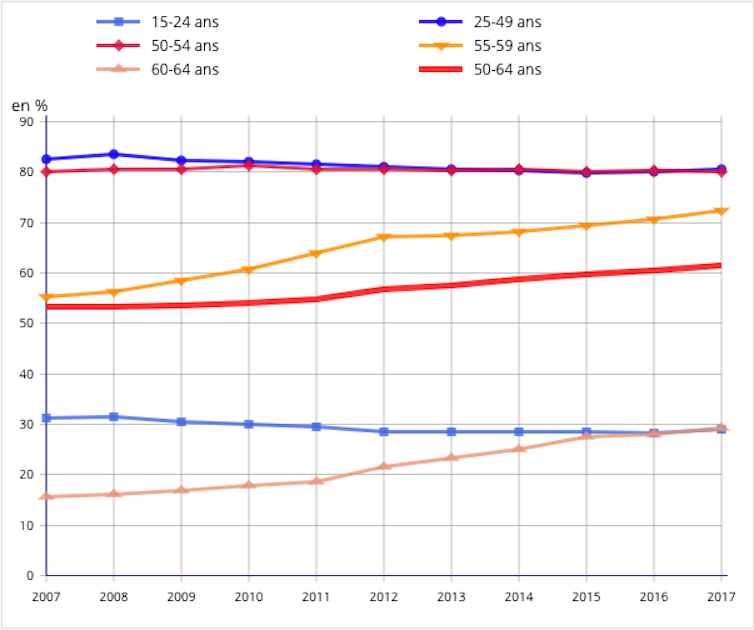

Since the early 2000s, there has been an increase in the number of older people in employment, following the increase in the minimum legal retirement age and in the number of years of contributions, as well as the abolition of early retirement and job-seeking exemptions. Indeed, the lengthening of workers' horizons on the job market has benefited their employability well before the age of 60: the average employment rate between the ages of 50 and 59 has risen by around 10 points over this period, despite a lacklustre economic climate.

Encouraging vocational training

This raises the question of the nature, or "quality", of the jobs occupied. Polarization is a particularly well-studied economic phenomenon today, characterizing the disappearance of so-called routine jobs (typically referring to the tasks performed by white-collar and blue-collar workers), to the benefit, on the one hand, of so-called complex, well-paid jobs, referring to the performance of managerial functions and with a strong cognitive component, and on the other hand (to a lesser extent) of low-wage manual jobs (typically linked to personal services).

And therein lies the rub: while for the 30-49 age group, the share of complex jobs in non-agricultural employment has risen by 8 points since the early 2000s to reach almost 32%, as a counterpart to the observed decline in the share of routine jobs, we have not seen this same "upmarket" trend among the 50-59 age group: the share of complex jobs, like that of routine and manual jobs, has remained stable for them.

Vocational training must therefore be at the heart of the measures to accompany the reform of the pension system, with genuine financial support offered to companies that offer to train their employees in the second half of their careers.

How can this policy be financed? Precisely by taxing the most affluent retirees, which would be a fair return and restore a certain intergenerational equity. Of course, this will require a bit (a lot) of education to make the people concerned understand the legitimacy of such a measure.

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Picture on freepik